How to diagnose cerebral palsy in infants

A cerebral palsy diagnosis in infants involves recognizing early developmental delays and performing specialized medical evaluations. Health care providers monitor a baby’s growth, motor skills, and muscle tone during routine checkups.

A cerebral palsy diagnosis in infants involves recognizing early developmental delays and performing specialized medical evaluations. Health care providers monitor a baby’s growth, motor skills, and muscle tone during routine checkups.

These are 3 early signs of cerebral palsy in newborn babies:

- Stiff or floppy muscles

- Challenges with movement

- Delayed milestones

If your child is showing signs of cerebral palsy, it’s important to consult a medical professional as soon as possible. Early cerebral palsy detection allows treatment to begin promptly, which can improve your child’s development and quality of life.

Unfortunately, caring for a child with cerebral palsy can feel overwhelming, with families often facing emotional and financial challenges. This may include therapy costs, medical equipment, and time away from work.

Cerebral palsy is sometimes caused by preventable complications during childbirth. If medical negligence led to your child’s condition, a cerebral palsy lawsuit can help cover these costs and provide long-term support.

Our team has helped families nationwide secure over $1 billion from birth injury lawsuits, including those involving CP.

Find out if we can help your family by getting a free case review right now.

What parents might notice before a cerebral palsy diagnosis

Parents often notice early symptoms of cerebral palsy when their child has trouble reaching milestones.

Early signs that may lead to a diagnosis of cerebral palsy include:

- Difficulty controlling head movements

- Favoring one hand or one side of the body

- Infant reflexes lasting longer than would be expected

- Poor eye contact or difficulty tracking objects

- Trouble grasping or holding onto items

- Unable to roll over by the expected age

- Unusual posture or movement patterns

If you notice delays, tell your child’s doctor. They may recommend further evaluation or referral to a specialist for additional testing.

If you’re worried about your child’s development, take our short milestone quiz.

IS YOUR CHILD MISSING DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES?

Take Our Milestones Quiz

Taking note of your child’s physical, social, and emotional skills can help you determine if they potentially suffered from an injury at birth. An early diagnosis can help your child get the treatment they need as soon as possible.

Q1: How old is your child?

0-2 MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Can your child hold their head steadily on their own?

- Q3: Can your child push themselves up when they are lying on their stomach?

- Q4: Has your child started to make smoother movements with their arms and legs?

- Q5: Does your child smile at other people?

- Q6: Can your child bring their hands to their mouth?

- Q7: Does your child turn their head when they hear a noise?

- Q8: Does your child coo or make gurgling noises?

- Q9: Does your child follow things with their eyes?

- Q10: Does your child try to look at their parents or caregivers?

- Q11: Does your child show boredom, cry, or fuss when engaged in an activity that hasn’t changed in a while?

3-4 MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Can your child hold their head steadily on their own?

- Q3: Does your child push down on their legs when their feet are on a flat surface?

- Q4: Has your child started to roll over from their stomach to their back?

- Q5: Can your child hold and shake a toy such as a rattle?

- Q6: Does your child bring their hands to their mouth?

- Q7: Does your child play with people and start to cry when the playing stops?

- Q8: Does your child smile spontaneously, especially at people?

- Q9: Does your child copy some movements and facial expressions of other people?

- Q10: Does your child babble with expressions and copy sounds they hear?

- Q11: Does your child cry in different ways to show hunger, pain, or tiredness?

- Q12: Does your child respond to affection like hugging or kissing?

- Q13: Does your child follow moving things with their eyes from side to side?

- Q14: Does your child recognize familiar people at a distance?

5-6 MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Can your child roll over on both sides (front to back/back to front)?

- Q3: Has your child begun to sit without support?

- Q4: Does your child rock back and forth?

- Q5: Can your child support their weight on their legs (and perhaps bounce) when standing?

- Q6: Has your child begun to pass things from one hand to the other?

- Q7: Does your child bring objects such as toys to their mouth?

- Q8: Does your child know if someone is not familiar to them and is a stranger?

- Q9: Does your child respond to other people’s emotions, such as a smile or a frown?

- Q10: Does your child enjoy looking at themselves in the mirror?

- Q11: Does your child look at things around them?

- Q12: Does your child respond to sounds they hear by making sounds themselves?

- Q13: Does your child make sounds to show joy or displeasure?

- Q14: Does your child respond to their own name?

- Q15: Has your child started to string vowels together, such as "ah," "eh," or "oh," or started to say consonant sounds such as "m" or "b"?

- Q16: Has your child begun to laugh?

7-9 MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Can your child crawl?

- Q3: Can your child stand while holding on to something to support them?

- Q4: Can your child sit without support?

- Q5: Can your child pull themselves up to stand?

- Q6: Does your child play peekaboo?

- Q7: Can your child move things from one hand to the other?

- Q8: Can your child pick small things up, such as a piece of cereal, with their thumb and index finger?

- Q9: Does your child look for things that they see you hide?

- Q10: Does your child watch the path of something as it falls?

- Q11: Does your child show fear when around strangers?

- Q12: Does your child become clingy with adults who are familiar to them?

- Q13: Does your child have favorite toys?

- Q14: Does your child use their fingers to point?

- Q15: Does your child understand “no”?

- Q16: Does your child make a lot of repetitive sounds, such as “mamama” or “bababa”?

- Q17: Does your child copy the sounds and gestures of other people?

10-12 MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Can your child stand alone with no support?

- Q3: Does your child walk while holding on to furniture?

- Q4: Can your child take a few steps without holding on to anything?

- Q5: Can your child get into a sitting position without any help?

- Q6: Does your child bang two things together when playing?

- Q7: Does your child poke with their index finger?

- Q8: Has your child started to use things like hairbrushes or drinking cups correctly?

- Q9: Does your child find hidden objects easily?

- Q10: Does your child play peekaboo or pat-a-cake?

- Q11: Does your child become shy or nervous around strangers?

- Q12: Does your child repeat actions or sounds to get attention?

- Q13: Does your child put out an arm or leg to help when getting dressed?

- Q14: Does your child cry when a parent leaves the room?

- Q15: Does your child show that they have favorite things or people?

- Q16: Does your child show fear?

- Q17: Does your child say things such as “mama,” “dada,” or “uh-oh”?

- Q18: Does your child try to say the words you say?

- Q19: Has your child started to use gestures like waving or shaking their head “no”?

13-18 MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Can your child walk by themselves?

- Q3: Does your child walk up stairs and run?

- Q4: Does your child pull toys while walking?

- Q5: Can your child drink from a cup on their own?

- Q6: Can your child eat with a spoon on their own?

- Q7: Can your child help undress themselves?

- Q8: Does your child have occasional temper tantrums?

- Q9: Does your child show affection to familiar people?

- Q10: Does your child become clingy in new situations?

- Q11: Does your child explore their environment alone with parents close by?

- Q12: Can your child say several single words?

- Q13: Can your child say and shake their head “no”?

- Q14: Does your child point to show things to other people?

- Q15: Does your child scribble?

- Q16: Does your child know what ordinary products such as phones, spoons, and brushes are used for?

- Q17: Can your child follow one-step commands such as “sit down” or “stand up”?

- Q18: Does your child play with a doll or stuffed animal by pretending to feed it?

19-23 MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Has your child begun to run?

- Q3: Has your child kicked a ball?

- Q4: Can your child climb down and onto furniture on their own?

- Q5: Can your child walk up and down stairs while holding on?

- Q6: Can your child stand on their tiptoes?

- Q7: Has your child thrown a ball overhand?

- Q8: Does your child copy others, especially people older than them?

- Q9: Does your child get excited around other children?

- Q10: Has your child shown more independence as they've aged?

- Q11: Does your child do what they were told not to do and become defiant?

- Q12: Does your child point to things when they are named?

- Q13: Does your child know names of familiar people or body parts?

- Q14: Does your child say 2 to 4-word sentences?

- Q15: Does your child repeat words they hear?

- Q16: Does your child complete sentences and rhymes in familiar books?

- Q17: Does your child name items in books, such as dogs, cats, and birds?

- Q18: Does your child play simple pretend games?

- Q19: Has your child started to use one hand more than the other?

- Q20: Has your child begun to sort shapes and colors?

- Q21: Does your child follow 2-step instructions, such as “pick up your hat and put it on your head?”

24+ MONTHS DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES QUIZ

- Q2: Can your child run easily?

- Q3: Can your child climb?

- Q4: Can your child walk up and down stairs with one foot on each step?

- Q5: Can your child dress and undress themselves?

- Q6: Does your child show affection for friends without being told?

- Q7: Does your child take turns when playing games?

- Q8: Does your child show concern when others are crying?

- Q9: Does your child understand the idea of “mine" and "theirs"?

- Q10: Does your child show many different emotions?

- Q11: Does your child copy adults and friends?

- Q12: Does your child separate easily from their parents?

- Q13: Does your child get upset when there is a major change in their routine?

- Q14: Does your child say words such as “I,” “me,” “we,” “you,” and some plural nouns?

- Q15: Can your child say their first name, age, and gender?

- Q16: Can your child carry on a conversation with 2 to 3 sentences?

- Q17: Can your child work toys with buttons and other moving parts?

- Q18: Does your child play pretend with dolls, animals, or people?

- Q19: Can your child finish 3 or 4 piece puzzles?

- Q20: Can your child copy a circle when drawing?

- Q21: Can your child turn pages of a book one page at a time?

- Q22: Can your child turn door handles?

Tests used for diagnosing cerebral palsy

Certain cerebral palsy tests can identify brain abnormalities linked to the condition and help support a diagnosis. Learn more about imaging tests used for a diagnosis of cerebral palsy below.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

An MRI creates detailed 3D images of the brain, helping doctors spot irregularities linked to motor function issues in babies and children.

This safe and painless cerebral palsy brain scan is often used when early symptoms appear.

Does cerebral palsy show on an MRI?

Cerebral palsy does not directly show up on an MRI, but an MRI can reveal abnormalities or brain damage associated with the condition.

During an MRI, the child lies on a table that slides into a tunnel-shaped scanner. The machine uses a strong magnet and radio waves to capture black-and-white images of the brain.

The process can take up to an hour, and young children may need sedation to remain still for accurate results.

MRI tests can help determine the underlying cause of CP, like brain injury or abnormal development. Early imaging plays a crucial role in guiding a cerebral palsy diagnosis and determining treatment options.

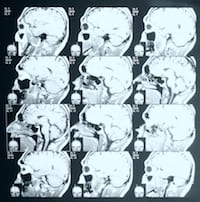

Computed tomography (CT)

CT scans create cross-sectional images of a child’s brain and are often used to evaluate conditions that may resemble cerebral palsy.

The procedure takes about 20 minutes and produces images similar to X-rays, offering views from multiple angles for a detailed examination of brain structures.

A CT scan cannot directly confirm a cerebral palsy diagnosis. However, it can detect issues like head injuries and brain bleeds, including intracranial or intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH).

It can also detect skull fractures and other brain abnormalities. These insights help rule out other conditions and provide clues about the cause and timing of a brain injury.

Cranial ultrasound

This imaging test isn’t as detailed as an MRI or CT scan, but it is often used because it is quick and easy for the patient. Cranial ultrasounds provide images of brain tissue, helping doctors identify potential signs of cerebral palsy.

This technique, which uses a probe to send high-frequency sound waves through the baby’s brain, is pain-free.

Cranial ultrasounds reveal bleeding in the brain and other conditions that can lead to a cerebral palsy diagnosis. Doctors use cranial ultrasounds to detect white matter damage, a common cause of cerebral palsy.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

An EEG measures the electrical activity of the brain. Children with seizures have distinct electrical patterns in their brains. Doctors use an EEG to diagnose epilepsy by recording those patterns.

During an EEG, patients will have a series of electrodes attached to their scalp so that the electrical energy can be measured.

Due to the link between cerebral palsy and epilepsy, a confirmed epilepsy diagnosis may increase the likelihood of a cerebral palsy diagnosis.

Other tests for children with CP

In addition to standard imaging tests, doctors may conduct other evaluations for conditions that often accompany the diagnosis of cerebral palsy, such as intellectual disabilities.

Some other tests for CP include:

- Hearing tests

- Intellectual tests

- Speech tests

- Vision tests

Doctors may also order blood tests to rule out hereditary conditions that affect motor function in children who might have cerebral palsy.

It’s important to have the whole picture to create an effective cerebral palsy treatment plan.

Cerebral palsy diagnosis by level of severity

A cerebral palsy diagnosis is often classified by severity as mild, moderate, or severe, providing insight into how the condition affects a person.

Doctors frequently use the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) to assess motor impairment. This allows them to provide a prognosis (or long-term health outlook), which includes the potential for improvement in skills like sitting independently and walking.

GMFCS: The 5 levels of severity in cerebral palsy

The GMFCS has five levels of motor impairment, from least severe (Level I) to most severe (Level V). The severity of a child’s initial diagnosis can help predict their future motor skills.

- Level I: Fully independent, can perform most physical activities normally with only slight problems in balance or coordination

- Level II: Trouble balancing on uneven surfaces, requires use of railings when climbing stairs, but can walk independently for the most part; minimal ability in running and jumping

- Level III: Requires assistive devices, like crutches, a walker, or a manual wheelchair; may be able to climb stairs using railing

- Level IV: Ability to walk is severely affected, most likely using a wheelchair to get around

- Level V: Significant restrictions in voluntary control; cannot walk, sit, or stand independently

The chart below is based on a study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association. It shows the approximate age when motor development begins tapering off.

Motor potential by age and GMFCS level

Potential to improve motor skills

A child’s level of impairment based on the GMFCS may change as they get older. As a child develops, motor impairment can improve, so they may be reclassified at a less severe level of impairment.

Children reach most of their motor development potential early in life. For children with cerebral palsy, the severity of their condition limits this potential.

For example, a child with Level IV movement problems may learn to sit unsupported by 3 years old, but their motor development is likely to taper off at this age.

A child with Level II movement problems, however, may sit by 18 months and eventually start walking before their motor function potential is reached.

Medical specialists involved in a cerebral palsy diagnosis

Getting an official cerebral palsy diagnosis often requires input from a team of doctors and specialists. Each plays an important role in understanding your child’s condition.

These specialists generally contribute to a diagnosis of cerebral palsy:

- Developmental pediatrician: Monitors physical and cognitive milestones to assess delays or unusual patterns

- Pediatric neurologist: Evaluates brain development to identify abnormalities or injuries affecting movement and muscle control

- Physical and occupational therapists: Examine motor skills, muscle tone, and movement to identify areas of concern

When choosing a specialist, look for one who has experience with cerebral palsy and ask for recommendations from your pediatrician. A knowledgeable team can provide the support your child needs.

Diagnosing cerebral palsy can be difficult, but your concerns matter. At Cerebral Palsy Guide, our on-staff registered nurses are here to help.

Connect with a nurse today for free, with no obligation.

Early cerebral palsy diagnosis tips for parents

Identifying the signs of cerebral palsy early can make a big difference in getting your child the care they need. Learn tips for recognizing potential symptoms and understanding when to seek help.

Cerebral palsy symptoms to watch for in babies

Cerebral palsy symptoms often vary depending on severity, but parents should watch for these common signs.

These are 3 early warning signs of a cerebral palsy diagnosis:

- Difficulty sitting or holding their head up at the expected age

- Unusual muscle tone, such as stiffness or floppiness

- Favoring one side of the body, like using only one hand to reach for objects

Mild cases may show subtle signs, while severe cases can significantly affect movement and coordination. Talk to your child’s pediatrician if you’re concerned.

Milestone delays linked to cerebral palsy diagnosis

Missed developmental milestones can be concerning for any parent. Delays in key skills may indicate motor control challenges often linked to cerebral palsy.

The chart below shows some milestones and typical ages.

| Developmental milestone | Expected age range |

|---|---|

| Holding up their head | 2 to 4 months |

| Rolling over | 4 to 6 months |

| Grasping or holding objects | 4 to 6 months |

| Crawling | 7 to 10 months |

| Sitting independently | 7 to 10 months |

| Standing or pulling up | 7 to 12 months |

| Walking | 9 to 18 months |

While delays alone don’t confirm a cerebral palsy diagnosis, discussing them with your child’s doctor is an important step.

When is cerebral palsy diagnosed?

The cerebral palsy diagnosis age is usually between 1 and 2 years, although the timing can vary depending on the severity of symptoms.

Children with more pronounced motor difficulties may receive a diagnosis earlier, while milder cases might not be identified until delays become more apparent as the child grows.

In some cases, a definitive diagnosis of cerebral palsy may not occur until a child is 3 or older.

Early cerebral palsy screening for high-risk infants

Infants born preterm, with low birth weight, or who experienced complications during birth, such as oxygen deprivation, are at a higher risk for cerebral palsy.

Developmental monitoring and screenings are recommended for infants at risk. Pediatricians assess motor skills, muscle tone, reflexes, and milestones during regular checkups, often at 9, 18, and 24 months.

Early detection in high-risk infants can lead to timely interventions and better outcomes. If concerns arise, doctors may suggest further evaluations or refer a patient to a specialist.

Challenges of diagnosing cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy can be challenging to diagnose, especially in young children. Early signs often overlap with normal developmental reflexes or other conditions, making it harder to identify CP, particularly in mild cases.

Reasons why cerebral palsy may be difficult to diagnose include:

- Clear signs may not appear until later in development

- Early symptoms often mimic other developmental conditions

- Symptoms can vary greatly between children

Additionally, some children with early developmental delays from brain injuries may recover, adding to the complexity of diagnosing cerebral palsy.

Monitoring motor skill development is a key step toward ruling out other conditions. For example, transient idiopathic dystonia, often seen in premature infants, causes movement issues similar to CP but usually resolves by age one.

Doctors are cautious about diagnosing CP in children under 18 months to avoid unnecessary stress for parents while ensuring an accurate diagnosis. However, this could force parents to be left worrying about undiagnosed cerebral palsy in their child.

Next steps after a cerebral palsy diagnosis

A cerebral palsy diagnosis can be life-altering, but there are steps to help you and your child move forward.

Start by focusing on early intervention programs like physical therapy to support your child’s development. If you’re unsure about your child’s cerebral palsy diagnosis, consider getting a second opinion from a specialist to feel confident in your child’s care plan.

For many families, the best path forward after a cerebral palsy diagnosis is seeking compensation from a lawsuit. If medical negligence caused your child’s condition, a cerebral palsy settlement can provide the resources to cover treatment costs and ongoing care.

This financial support can help ensure your child receives the therapies and services they need for the best possible future.

Our legal partners have recovered over $1 billion for families nationwide impacted by preventable birth injuries.

Call one of our caring patient advocates at (855) 220-1101 or get a free case review to see if we can help.